WHEC Practice Bulletin and Clinical Management Guidelines for healthcare providers.

Educational grant provided by Women’s Health and Education Center (WHEC).

The inadequate management of pain is the result of several factors related to both patients and

clinicians. Education and open communication are the keys to overcoming these barriers. Every

member of the healthcare team should reinforce accurate information about pain management with

patients and families. The clinician should initiate conversations about pain management, especially

regarding the use of opioids, as few patients will raise the issue themselves or even express their

concerns unless they are specifically asked (1). Encouraging patients to be honest about pain and

other symptoms is also vital. Clinicians should ensure that patients understand that pain is

multi dimensional and emphasize the importance of talk ing to a member of the healthcare team about

pos sible causes of pain, such as emotional or spiritual distress. The healthcare team and patient

should explore psychosocial and cultural factors that may affect self-reporting of pain, such as

concern about the cost of medication. The prevalence of pain at the end of life varies, with ranges of

8% to 96% being reported (2). Because pain is frequently encountered in the palliative and hospice

care environments, and knowledge of appropriate diagnosis and alleviation is vital to all members of

the interdisciplinary team.

The purpose of this End-of-Life Care Series is to provide an overview of the assessment

and management of pain in the end of life, focusing on the components integral to providing optimum

care. This review discusses the etiology of pain at the end of life and issues in effective pain

management; assessment of pain accurately through use of clinical tools and other strategies,

including the use of an interpreter; and select appropriate pharmacologic and/or non-pharmacologic

therapies to manage pain in patients during the end-of-life period.

Issues in Effective Pain Management

Pain can be caused by a multitude of factors. For patients with cancer, the most common source

of pain is the underlying lesion or disease process itself. In addition, pain is frequently exacerbated by

other physical symptoms and by psychosocial factors, such as anxiety or depression (3). Cultural

and demographic factors may also contrib ute to lack of effective pain management. Expres sion of

pain and the use of pain medication differ across cultures. For example, Hispanic and Filipino

patients have been shown to be reluctant to report pain because of fear of side effects or addiction

(2). Some studies have shown that black and His panic patients in cancer centers were less likely to

have effective analgesics prescribed (4). Even when effective opioids have been prescribed, access

may be difficult, as inadequate supplies of opioids are more likely in pharmacies in primarily nonwhite

neighborhoods (3), (4). Communication with patients regarding level of pain is a vital aspect of caring

for patients in the end of life. When there is an obvious disconnect in the communication process

between the practitioner and patient due to the patient’s lack of proficiency in the English language, an

interpreter is required. Patients’ attitudes that are barriers to effective pain relief include:

- Fear of addiction to opioids;

- Worry that if pain is treated early, there will be no options for treatment of future pain;

- Anxiety about unpleasant side effects from pain medications;

- Fear that increasing pain means that the disease is getting worse;

- Desire to be a “good” patient;

- Concern about the high cost of medications.

There are several other ways clinicians can allay patients’ fears about pain medication:

- Assure patients that the availability of pain relievers cannot be exhausted; there will always be

medications if pain becomes more severe; - Acknowledge that side effects may occur, but emphasize that they can be managed promptly and

safely and that some side effects will abate over time; - Explain that pain and severity of disease are not necessarily related.

Encouraging patients to be honest about pain and other symptoms is also vital.

Pain Assessment

As the fifth vital sign, pain should be assessed as frequently as the other vital signs and the

findings should be well documented, for easy reference by all members of the healthcare team (5).

Pain is a subjective experience, and as such, the patient’s self-report of pain is the most reliable

indicator. Research has shown that pain is underestimated by healthcare professionals and

overestimated by fam ily members (5). Therefore, it is essential to obtain a pain history directly from

the patient, when possible, as a first step toward determining the cause of the pain and selecting

appropriate treatment strategies. When the patient is unable to orally communicate, other strategies

must be used to determine the characteristics of the pain, as will be discussed. Questions should be

asked to elicit descriptions of the pain characteristics, including its location, distribution, quality,

temporal aspect, and inten sity. In addition, the patient should be asked about aggravating or alleviating

factors. Pain is often felt in more than one area, and physicians should attempt to discern if the pain

is focal, multifocal, or generalized. Focal or multifocal pain usually indi cates an underlying tissue

injury or lesion, whereas generalized pain could be associated with damage to the central nervous

system. Pain can also be referred, usually an indicator of visceral pain.

The quality of the pain refers to the sensation experienced by the patient, and it often suggests

the pathophysiology of the pain (6). Pain that is well localized and described as aching, throbbing,

sharp, or pressure-like is most likely somatic noci ceptive pain. This type of pain is usually related to

damage to bones and soft tissues. Diffuse pain that is described as squeezing, cramping, or

gnawing is usually visceral nociceptive pain. Pain that is described as burning, tingling, shooting, or

shock-like is neuropathic pain, which is generally a result of a lesion affecting the nervous system.

Temporal aspects of pain refer to its onset (acute, chronic, or “breakthrough”). A recent onset

char acterizes acute pain, and there are accompanying signs of generalized hyperactivity of the

sympa thetic nervous system (diaphoresis and increased blood pressure and heart rate). Acute pain

usu ally has an identifiable, precipitating cause, and appropriate treatment with analgesic agents will

relieve the pain. When acute pain develops over several days with increasing intensity, it is said to be

subacute. Episodic, or intermittent, pain occurs during defined periods of time, on a regular or

irregular basis (7). Chronic pain is defined as pain that persists for at least three months beyond the

usual course of an acute illness or injury. Such pain is not accompanied by overt pain behaviors

(grimacing, moaning) or evidence of sympathetic hyperactivity. “Breakthrough” is the term used to

describe transitory exacerbations of severe pain over a baseline of moderate pain (8). Break through

pain can be incident pain or pain that is precipitated by a voluntary act (such as movement or

coughing), or can occur without a precipitating event. Often, breakthrough pain is a consequence of

inadequate pain management.

Documentation of pain intensity is the key, as several treatment decisions depend on the intensity

of the pain. For example, severe, intense pain requires urgent relief, which affects the choice of drug

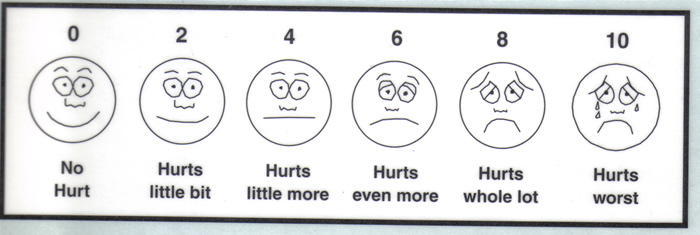

and the route of administration. Many assess ment tools have been developed, and among the more

commonly used tools are the Wisconsin Brief Pain Questionnaire, the Memorial Pain Assessment

Card, and the McGill Pain Questionnaire (short form) (9). Simpler forms of measuring pain include

numerical rankings (patients rate pain on a scale of 0 to 10), and visual analogue scales (patients

rate pain on a line from 0 to 10). Verbal rating scales, which enable the patient to describe the pain as

“mild,” “moderate,” or “severe,” have also been found to be effective. Some patients, however, may

have difficulty rating pain using even the simple scales. In an unpublished study involving 11 adults

with cancer, the Wong-Baker FACES scale, developed for use in the pediatric setting, was found to

be the easiest to use among three pain assessment tools that include faces to assess pain (7).

Wong-Baker FACES Pain Scale Rating

0-10 Pain Scale; Mild, Moderate or Severe

Note: equivalence between these two scales is:

1. No pain observed or patient denies pain – 0 out of 10

2. Mild pain – 1 to 3 out of 10

3. Moderate pain – 4 to 7 out of 10

4. Severe pain – 8 to 10 out of 10

Functional assessment is important. The health care team should observe the patient to see how

pain limits movements and should ask the patient or family how the pain interferes with normal

activities. Determining functional limitations can help enhance patient compliance in reporting pain

and adhering to pain-relieving measures, as clini cians can discuss compliance in terms of achieving

established functional goals (1). Physical examination can be valuable in deter mining an underlying cause of pain. Examination of painful areas can detect evidence of trauma, skin breakdown, or

changes in osseous structures. Auscultation can detect abnormal breath or bowel sounds;

percussion can detect fluid accumulation; and palpation can reveal tenderness. A neurologic

examination should also be carried out to evaluate sensory and/or motor loss and changes in

reflexes. During the examination, the clinician should watch closely for nonverbal cues that suggest

pain, such as moaning, grimacing, and protective move ments. These cues are especially important

when examining patients who are unable to verbally communicate about pain.

Pain Assessment in Non-Verbal Patient/Advanced Dementia Scale

| 0 | 1 | 2 | Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breathing

Independent |

Normal | Occasional labored breathing. Short period of hyperventilation. |

Noisy labored breathing. Long period of hyperventilation. Cheyne-strokes respirations. |

|

| Negative Vocalization | None | Occasional moan or groan. Low level of speech with a negative or disapproving quality. | Repeated troubled calling out.

Loud moaning or groaning. Crying. |

|

| Facial Expression | Smiling, or Inexpressive. | Sad. Frightened. Frown. | Facial grimacing. | |

| Body Language | Relaxed. | Tense.

Distressed pacing. Fidgeting. |

Rigid. Fists clenched, knees pulled up.

Pulling or pushing away. Striking out. |

|

| Consolability | No need to console. | Distracted or Reassured by voice or touch. | Unable to console, distract or reassure. | |

| Document Intervention | Total, |

Key: 0-10 scale. Anything >4 requires medication for comfort

Pain Management

There is no evidence to support specific pain man agement interventions for patients with some

life-limiting diseases, such as heart failure or dementia (10). There is, however, strong evidence to

support approaches to treat cancer pain; namely, non-steroi dal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs),

opioids, and radiotherapy (10). Bisphosphonates have been effective for bone pain (10).

The overall objectives of pharmacologic manage ment of pain include (11):

- Selection of the appropriate drug, dose, route, and interval;

- Aggressive titration of the drug dose;

- Prevention of pain and relief of breakthrough pain;

- Use of appropriate co-analgesic medications;

- Prevention and management of side effects.

Achieving the first four of these objectives is best done with use of the World Health Organization

(WHO) three-step analgesic ladder, which designates the type of analgesic agent based on the

severity of pain (12). Step 1 of the WHO ladder involves the use of non-opioid analgesics, with or

without an adjuvant (co-anal gesic) agent, for mild pain (pain that is rated 1 to 3 on a 10-point scale).

Step 2 treatment, recom mended for moderate pain (score of 4 to 6), calls for a low dose of an opioid,

which may be used in combination with a step 1 non-opioid analgesic for unrelieved pain. Step 3

treatment is reserved for severe pain (score of 7 to 10) or pain that persists after Step 2 treatment.

Opioids are the optimum choice of drug at Step 3, often in higher doses than at Step 2. At any step,

non-opioids and/or adjuvant drugs may be helpful. Before describing the various non-opioid and

opioid analgesic agents, two important principles must be noted. First, treatment according to the

WHO analgesic ladder should correspond with the inten sity of pain as described by the patient,

regardless of whether treatment at a previous step was car ried out. For example, if a patient has

severe pain when initially assessed, treatment should begin at Step 3, not Step 1. Second,

analgesics must be administered on around-the-clock dosing, not on an as-needed basis. Not only is

this approach more effective at controlling pain but it also avoids unnecessary pain as a prompt for

the next dose.

Non-opioid analgesics include aspirin, acetamino phen, and NSAIDs. They are primarily used for

mild pain (Step 1 of the WHO ladder) and may also be helpful as co-analgesics at Steps 2 and 3.

Acetaminophen is among the safest of analgesic agents, but it has essentially no anti-inflammatory

effect. When given at high doses (4,000 mg per day), the drug can cause liver dysfunction; there fore,

it should be avoided or used at lower doses for patients who have renal insufficiency or liver failure

(13). NSAIDs are most effective for pain associated with inflammation. Among the commonly used

NSAIDs are ibuprofen, naproxen, and indometha cin. There are several classes of NSAIDs, and the

response differs among patients; trials of drugs for an individual patient may be necessary to

deter mine which drug is most effective (9), (15). NSAIDs inhibit platelet aggregation, increasing the risk

of bleeding, and also can damage the mucosal lining of the stomach, leading to gastrointestinal

bleed ing (38). There is a ceiling effect to the non-opioid analgesics; that is, there is a dose beyond

which there is no further analgesic effect. In addition, many side effects of non-opioids can be severe

and may limit their use or dosing.

Management of Pain in Adults According To the World Health Organization (WHO) Ladder

| Drug | Typical Starting Dose and Routea | Onset of Action | Duration of Action (Hours) |

| WHO Step 1: Mild Pain (score of 1-3 on a 10-point scale) |

|||

| Aspirin | 650 mg PO | 30 min | 3-4 |

| Acetaminophen | 650 mg PO | 15 to 30 min | 3-4 |

| NSAIDs

Ibuprofen Naproxen Indomethacin Piroxicam |

200-800 mg PO 250-275 mg PO 25-75 mg PO 10-20 mg PO |

30 min 60 min 30 min to several hrs Several hrs |

4-6 6-12 4-12 24 |

| Step 2: Moderate Pain (score of 4-6 on a 10-point scale) |

|||

| Acetaminophen combinations |

|||

| Plus codeine

Plus oxycodone Plus hydrocodone |

60 mg PO

5-10 mg PO 10 mg PO |

30 min

Unknown 30 to 60 min |

3-4

3-4 4-6 |

| Codeine | 30-60 mg PO

30 mg IV/SC |

30 to 45 min | 4-6 |

| Hydrocodone | 10-30 mg PO | 30 to 60 min | 4-8 |

| Morhpineb (immediate release) |

5-15 mg PO

2-10 mg/hr IV 4-15 mg SC |

30 min

10-30 min 10-15 min |

3-4

3-4 3-4 |

| Step 3: Severe Pain (score of >7 on a 10-point scale) |

|||

| Morphine (sustained release) | 15-30 mg PO | 60 min | 8-12 |

| Oxycodone (immediate release) | 5-10 mg PO | 10 to 15 min | 3-6 |

| Oxycodone (sustained release) | 10-20 mg PO | 30 min | 12 |

| Hydromorphone | 2-4 mg PO

0.3-1.5 mg IV |

15 to 30 min | 4-6

2-4 |

| Methadone | 5-10 mg PO

2.5-10 mg IV |

30 to 60 min | 4-8 |

| Levorphanol | 2-4 mg PO | 10 to 60 min | 6-8 |

| Fentanyl | 50-100 mcg IV

Transdermal patch |

5-10 min

12 to 24 hr |

Varies

48-72 |

| a Doses given are guidelines for opioid-naïve patients; actual doses should be determined on an individual basis.

b Also used in Step 3. NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; IV: intravenous; SC: subcutaneous; PO: per oral route. |

Moderate pain (Step 2) can be treated with analge sic agents that are combinations of

acetaminophen and an opioid, such as codeine, oxycodone, or hydrocodone. Strong opioids are used

for severe pain (Step 3). There is no conclusive evidence of the superior ity of one opioid over another

(16). Morphine, oxycodone, hydromorphone, and fentanyl are the most widely used opioids in the

United States (17). Morphine is the most commonly used opioid for Step 3, and its efficacy has been

established (17). Morphine is available in both immediate-release and sustained-release forms, and

the latter form can enhance patient compliance. The sustained-release tablets should not be cut,

crushed, or chewed, as this counteracts the sustained-release properties. The sustained-release

form of oxycodone (Oxy Contin) has been shown to be as safe and effective as morphine for cancer-

related pain, and it may be associated with less common side effects, especially hallucinations and

delirium (17). Oxycodone is also available in an immediate-release form (Roxicodone).

Hydromorphone and fentanyl are the most potent opioids; neither drug should be given to an opioid-

naïve patient. Hydromorphone, which is four times as potent as morphine, is available in immediate-

release form. An extended-release form of hydromorphone was approved by the FDA in 2004;

however, sales and marketing of the drug were suspended by the manufacturer in 2005 because of

the potential for severe side effects when taken with alcohol (18). Fentanyl is the strongest opioid

(approximately 80 times the potency of morphine) and is available as a transdermal drug-delivery

system (Duragesic) (18). Because peak delivery does not occur until 12 hours, an alternate

analgesic must also be given initially. Transdermal fentanyl is helpful for patients who are unable (or

unwilling) to take an oral opioid (16). Because of its potency, fentanyl must be used with extreme

care, as deaths have been associated with its use. Physicians must emphasize to patients and their

families the importance of following prescribing information closely, and members of the healthcare

team should monitor the use of the drug.

Equianalgesic Doses for Fentanyl Transdermal Patch (37)

| Dose of Fentanyl | Total Dose of Morphine | |

| Oral Dose | Parenteral Dose | |

| 25 mcg/hr | 25-65 mg/24 hr | 8-22 mg/24 hr |

| 50 mcg/hr | 65-115 mg/hr | 23-37 mg/24 hr |

| 75 mcg/hr | 116-150 mg/hr | 38-52 mg/24 hr |

| 100 mcg/hr | 151-200 mg/hr | 53-67 mg/24 hr |

| 125 mcg/hr | 201-225 mg/hr | 68-82 mg/24 hr |

| 150 mcg/hr | 226-300 mg/hr | 83-100 mg/24 hr |

The use of methadone to relieve pain has increased substantially over the past few years,

moving from a second-line or third-line drug to a first-line medication for severe pain in patients with

life-limiting diseases (19). Physicians must be well educated about the pharmacologic proper ties of

methadone, as the risk for serious adverse events, including death, is high when the drug is not

administered appropriately (20). One chal lenge in using methadone lies in the discrepancy between

its duration of effect (four to six hours) and its elimination half-life (range: 15 to 40 hours; average: 24

to 36 hours) (21). Consequently, if the dose of methadone is increased too rapidly or administered too

frequently, toxic accumula tion of the drug can cause respiratory depression and death. When using

methadone, extreme care must be taken when titrating the drug, and close evaluation of the patient is

necessary. Propoxyphene is an opioid that is chemically similar to methadone. It is not recommended

for use because of toxicity even at therapeutic doses and a lack of efficacy compared with placebo or

acetaminophen (1), (9), (15). Similarly, mep eridine should not be used in the palliative care setting

because of limited efficacy and potential for severe toxicity. Agonist-antagonist opioids (nalbuphine,

butorphanol, and pentazocine) are not recommended for use with pure opioids, as they compete with

them, leading to possible withdrawal symptoms. Unlike non-opioids, opioids do not have a ceiling

effect, and the dose can be titrated until pain is relieved or side effects become unmanageable. For

an opioid-naïve patient or a patient who has been receiving low doses of a weak opioid, the initial

dose should be low. Immediate-release morphine, hydromorphone, and oxycodone are the best

options (9). For a patient who has been taking a strong opioid and pain persists, the dose may be

titrated up on a daily basis until pain is controlled. More than one route of opioid administration will be

needed by many patients during end-of-life care, but in general, opioids should be given orally, as this

route is the most convenient and least expen sive. For patients who have difficulty swallowing, the

transdermal route is preferred to the parenteral route. Intravenous and subcutaneous routes should

be reserved for patients who have pain crises or considerable intermittent pain (22). Intramuscular

injections should be avoided.

Extra (rescue) doses of opioids are necessary for breakthrough pain. No individual opioid has

been shown to be better than another for breakthrough pain (23). The most appropriate option is the

immediate-release form of the same opioid in rou tine use for pain control. This approach increases

efficacy while minimizing the risk of adverse effects. However, if fentanyl or methadone is the

routinely used drug, morphine or hydromorphone should be used for rescue doses. The rescue dose

should be 5% to 15% of the 24-hour dose (22). Rescue doses may be repeated at intervals

determined by the route of administration; oral doses may be repeated every hour, subcutaneous

doses may be given every 30 minutes, and intrave nous doses may be given every 5 to 10 minutes. If

three or more rescue doses are needed in a 24-hour period, the dose of the routinely used drug

should be titrated 25% to 100%, according to the intensity of the pain (22). There is limited evidence

that transmucosal fentanyl provides more rapid pain relief for breakthrough pain than morphine.

When pain responds poorly to escalated doses of an opioid, other approaches should be considered,

including alternative routes of administration, use of alternate opioids (termed opioid rotation or opioid

switching), use of co-analgesics, and non- pharmacologic approaches. Opioid rotation has been

shown to offer improvement in more than 50% of patients who have chronic pain and a poor

response to one opioid (24). When changing the route of administration or the opioid, the dose of the

new opioid should be 50% to 75% of the equianalgesic dose (24). Evidence suggests that the

traditionally recommended equianalgesic doses for the fentanyl transdermal patch are sub-

therapeutic for patients with chronic cancer-related pain, and more aggressive approaches may be

warranted.

Side Effects of Opioids: Opioids are associated with many side effects, the most notable

of which is constipation, occurring in nearly 100% of patients. The universality of this side effect

mandates that once extended treatment with an opioid begins, prophylactic treatment with laxatives

must also be initiated. Tolerance to other side effects, such as nausea and sedation, usually develops

within three to seven days. Some patients may state that they are “allergic” to an opioid. It is

important for the physician to explore what the patient experienced when the drug was taken in the

past, as many patients misinterpret side effects as an allergy. True allergy to an opioid is rare (1), (9).

Patients and families also fear that high doses of opioids can hasten death (the so-called double

effect); this is unsubstantiated by research. When opioids are prescribed, careful documenta tion of

the patient’s history, examinations, treat ments, progress, and plan of care are especially important

from a legal perspective. This documen tation must provide evidence that the patient is functionally

better off with the medication than without (15). In addition, physicians must note evidence of any

dysfunction or abuse.

Adjuvant Agents: Adjuvant (co-analgesic) agents are often used in conjunction with

opioids and are usually consid ered after the use of opioids has been optimized (15). The primary

indication for these drugs is adjunctive because they can provide relief in specific situations,

especially neuropathic pain. Examples of adjuvant drugs are tricyclic antidepres sants,

corticosteroids, anticonvulsants, and local anesthetics (see table below). Tricyclic

antidepressants are recommended for burning, stinging pain that is continuous or when underlying

depression or insomnia is present (24). Another class of anti depressants, selective serotonin

reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), has been relatively ineffective as analge sic agents (25). Anticonvulsants

are suggested for neuropathic pain and lancinating, paroxysmal pain (25). Low doses of prednisone

have been found to be effective for vasculitic neuropathy, bone pain, and other cancer-related

pain.

ADJUVANT ANALGESICS

| Indications | Drugs | Typical Starting Dose * | Titration Recommendations |

| Spinal cord compression, malignant bone and nerve pain | Prednisone | 20-40 mg PO, daily in divided doses | |

| Dexamethasone | 4-16 mg PO, daily in divided doses | ||

| Dysesthetic and paroxysmal lancinating pain | Gabapentin | 300-900 mg PO, 3-times daily | Increase by 100-300 mg every 1 to 3 days |

| Phenytoin | 200-300 mg PO, daily | ||

| Carbamazepine | 800 mg PO, daily | Increase every 3 days | |

| Lamotrigine | 25 mg PO, daily | Increase by 25-50 mg/day per week | |

| Topiramate | 25-50 mg PO, daily | Increase by 25-50 mg/day per week | |

| Oxcarbazepine | 300 mg PO, 2 times daily | Increase by 300 mg every week | |

| Levetiracetam | 500 mg PO, 2 times daily | ||

| Neuropathic and musculoskeletal pain | Amitriptyline

Imipramine Doxepin Chlomipramine Desipramine Nortriptyline |

10-25 mg PO, daily at bedtime |

Increase to therapeutic dose of 50-150 mg daily in divided doses |

| Bone pain | Pamidronate | 90 mg IV (over 2 hr), monthly | |

| Visceral pain | Octreotide

Scopolamine |

100-600 mg IV or SC, daily

0.8-2.0 mg SC, daily |

|

| Second-line treatment of neuropathic pain (used with anticonvulsants) |

Baclofen |

5 mg PO, 2 times daily |

Increase by 5 mg every 3 days to reach target dose of 40-80 mg/24 hr |

| Neuropathic pain refractory to anticonvulsants and opioids |

Lidocaine |

1-3 mg/kg IV, as loading dose (over 20 to 30 min), followed by infusion of 0.5-2 mg/kg/hr | |

| Post-herpetic neuralgia | Capsaicin cream | 0.075% cream, 4 times daily |

*Doses given are guidelines; actual doses should be determined on an individual basis.

Non-Pharmacologic Management

Several non-pharmacologic approaches are thera peutic complements to pain-relieving

medication, lessening the need for higher doses and perhaps minimizing side effects. These

interventions can help decrease pain or distress that may be contrib uting to the pain sensation.

Approaches include palliative radiotherapy, complementary/alternative methods, manipulative and

body-based methods, and cognitive/behavioral techniques. The choice of a specific non-

pharmacologic intervention is based on the patient’s preference, which, in turn, is usually based on a

successful experience in the past.

Palliative radiotherapy is effective for managing cancer-related pain, especially bone metastases

(26). Bone metastases are the most fre quent cause of cancer-related pain; 50% to 75% of patients

with bone metastases will have pain and impaired mobility. External beam radiotherapy is the

mainstay of treatment for pain related to bone metastases. At least some response occurs in 70% to

80% of patients, and the median duration of pain relief has been reported to be 11 to 24 weeks. It

takes one to four weeks for optimal therapeutic results (26). However, palliative radiotherapy has

become a controversial issue. Although the benefits of pal liative radiotherapy are well documented

and most hospice and oncology professionals believe that palliative radiotherapy is important, this

treat ment approach is offered at approximately 24% of Medicare-certified freestanding hospices, with

less than 3% of hospice patients being treated (27). Reimbursement issues present a primary barrier

to the use of palliative radiotherapy, and the cost of the treatment is prohibitive for many hospices,

especially smaller ones. Among other barriers to the utilization of palliative radiotherapy are short life

expectancy, transportation issues, patient inconvenience, and lack of knowledge about the benefits of

palliative radiotherapy in the primary care community (28).

Two common complementary/alternative methods for pain relief are acupuncture and yoga.

Acupunc ture involves the insertion of needles beneath the skin to stimulate peripheral nerves to

provide pain relief. In general, relief occurs 15 to 40 minutes after stimulation. Relief seems to be

related to the release of endorphins and a susceptibility to hypnosis (1). The efficacy of acupuncture

for reliev ing pain has not been proven, as study samples have been small. However, it may be

beneficial for musculoskeletal or nerve pain (29). Hatha yoga is the branch of yoga most often used in

the medical context, and it has been shown to provide pain relief for patients who have osteoarthritis

and carpal tunnel syndrome but it has not been studied in patients at the end of life. Yoga may help

relieve pain indirectly in some patients through its effects on reducing anxiety, increasing strength and

flex ibility, and enhancing breathing (30). Yoga also helps patients feel a sense of control. Manipulative

and body-based methods include application of cold or heat, massage and vibra tion, positioning, and

exercise. The application of cold and heat are particularly useful for local ized pain and have been

found to be effective for cancer-related pain caused by bone metastases or nerve involvement, as

well as for prevention of breakthrough incident pain (1). Alternating application of heat and cold can be

soothing for some patients, and it is often combined with other non-pharmacologic interventions. Cold

can be applied through wraps, gel packs, ice bags, and menthol. It provides relief for pain related to

skeletal muscle spasms induced by nerve injury and inflamed joints. Cold application should not be

used for patients with peripheral vascular disease. Heat can be applied as dry (heating pad) or moist

(hot wrap, tub of water) and should be applied for no more than 20 minutes at a time, to avoid burn ing

the skin. Heat should not be applied to areas of decreased sensation or with inadequate vascular

supply, or for patients with bleeding disorders. Massage, which can be broadly defined as stroking,

compression, or percussion, has led to significant and immediate improvement in pain in the hos pice

setting (31). Both massage and vibration are primarily effective for muscle spasms related to tension

or nerve injury, and massage can be carried out with simultaneous application of heat or cold.

Massage may be harmful for patients with coagula tion abnormalities or thrombophlebitis.

Non-pharmacologic management of pain also includes cognitive/behavioral approaches such as

relaxation and breathing, imagery, and distractions. Focused relaxation and breathing can help

decrease pain by easing muscle tension. Progressive muscle relaxation, in which patients follow a

sequence of tensing and relaxing muscle groups, has enabled patients to feel more in control and to

experience less pain (1). This technique should be avoided if the muscle tensing will be too painful.

Focused relaxation and breathing help provide distraction from pain. Other methods of distrac tion

include reciting a poem, meditating with a calm phrase, watching television or movies, play ing cards,

visiting with friends, or participating in crafts. Imagery is among the most effective of the cognitive

strategies for pain relief and works espe cially well when it involves as many sites and senses as

possible (32). Some research has shown that the efficacy of music therapy is similar to that of

relaxation for relieving pain (32).

Music therapy and art therapy are also becoming more widely used as non-pharmacologic

options for pain management (33). Music therapy works best when guided by an individual trained in

using it who can involve patients in selecting music to hear, playing music on instruments, or song

writing. Research suggests that art therapy contributes to a patient’s sense of well-being (33).

Creating art helps patients and families to explore thoughts and fears during the end of life. An art

therapist can help the creators reflect on the implications of the art work. Art therapy is especially

helpful for patients who have difficulty expressing feelings with words, for physical or emotional reasons.

Acronym for Pain Assessment and Management

The ABCDE acronym was written by Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Services for cancer pain. Although this

acronym is very appropriate for patients at end of life, regardless of their underlying disease.

A = Ask about pain regularly. Assess pain systematically.

B = Believe the patient and family in their reports of pain and what relieves it.

C = Choose pain control options appropriate for the patient, family and setting.

D = Deliver interventions in a timely, logical and coordinated fashion.

E = Empower patients and their families. Enable them to control their course to the greatest extent

possible.

Legal and Ethical Issues Related to Pain Management

Fear of license suspension for inappropriate pre scribing of controlled substances is also

prevalent, and a better understanding of pain medication will enable physicians to prescribe

accurately, alleviat ing concern about regulatory oversight. Physicians must balance a fine line; on one

side, strict federal regulations regarding the prescription of schedule II opioids (morphine, oxycodone,

methadone, hydromorphone) raise fear of Drug Enforcement Agency investigation, criminal charges,

and civil lawsuits (34). Careful documentation on the patient’s medical record regarding the rationale

for opioid treatment is essential (34). On the other side, clinicians must adhere to the American

Medi cal Association’s Code of Ethics, which states that failure to treat pain is unethical. The code

states, in part: “Physicians have an obligation to relieve pain and suffering and to promote the dignity

and autonomy of dying patients in their care. This includes providing effective palliative treatment

even though it may foreseeably hasten death” (35). In addition, the American Medical Association

Statement on End-of-Life Care states that patients should have “trustworthy assurances that physical

and mental suffering will be carefully attended to and comfort measures intently secured” (35).

Physicians should consider the legal ramifications of inadequate pain management and

understand the liability risks associated with both inadequate treatment and treatment in excess. The

under-treat ment of pain carries a risk of malpractice liability, and this risk is set to increase as the

general popula tion becomes better educated about the availability of effective approaches to pain

management at the end of life (15). Establishing malpractice requires evidence of breach of duty and

proof of injury and damages. Before the development of various guidelines for pain management, it

was difficult to establish a breach of duty, as this principle is defined by non-adherence to the

standard of care in a designated specialty. With such standards now in existence, expert medical

testimony can be used to demonstrate that a practitioner did not meet established standards of care

for pain management. Another change in the analysis of malpractice liability involves injury and

damages. Because pain management can be considered as separate from disease treatment and

because untreated pain can lead to long-term physical and emotional damage, claims can be made

for pain and suffering alone, without wrongful death or some other harm to the patient (36).

Summary

Unrelieved pain is the greatest fear among patients with a life-limiting disease. This fear has been

substantiated by findings from studies demonstrat ing under-treatment of pain among patients with a

variety of chronic diseases and even for patients enrolled in palliative care or hospice programs.

Healthcare professionals have acknowledged that the treatment of pain is inadequate. Healthcare

professionals should strive to enhance their knowledge of key strategies to achieve high-quality pain

management at the end of life, as detailed in this course.

Suggested Reading

End-of-Life Decision Making

www.womenshealthsection.com/content/heal/heal022.php3

References

- Abrahm JL. A Physician’s Guide to Pain and Symptom Management in Cancer Patients. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2005

- Goudas LC, Bloch R, Gialeli-Goudas M, et al. The epidemiology of cancer pain. Cancer Invest 2005;23:182-190

- Skaer T. Transdermal opioids for cancer pain. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2006;4:24-28

- Anderson KO, Mendoza TR, Valero V, et al. Minority cancer patients and their providers: pain management attitudes and practice. Cancer 2000;88:1929-1938

- American Pain Society. Treatment of Pain at the End of Life. Available at www.ampainsoc.org Accessed on 21 April 2012

- Berger AM, Portenoy RK, Weissman DE (eds). Principles & Practice of Palliative Care & Supportive Oncology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002

- Hockenberry M, Wilson D. Wong’s Essentials of Pediatric Nursing. 8th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2008

- Lorenz KA, Lynn J, Dy SM, et al. Evidence for improving palliative care at the end of life: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2008;148(2):147-159

- Levy MH. Pain, general. In: ASCO Curriculum: Optimizing Cancer Care–The Importance of Symptom Management. Alexandria, VA: American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2001

- Qaseem A, Snow V, Shekelle P, et al. Evidence-based interventions to improve the palliative care of pain, dyspnea, and depression at the end of life: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2008;148(2):141-146

- Librach L. Pain management. In: Ian Anderson Continuing Education Program in End-of-Life Care. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto; 2000

- World Health Organization. WHO’s Pain Ladder. Geneva: Available at: www.who.int/cancer/palliative/painladder/en/ Accessed on 2 may 2012

- Celli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, et al. The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1005-1012

- Lanken PN, Terry PB, Delisser HM, et al. An official American Thoracic Society clinical policy statement: palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illnesses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177(8):912-927

- Bailey FA. Palliative Response. Available at www.palliative.uab.edu/wp-content/uploads/palliative_response/palliative-response.pdf Last accessed 30 April 2012

- Mc Cleane G, Smith HS. Opioids for persistent noncancer pain. Anesthesiol Clin 2007;25:787-807

- Wiffen P, McQuay HJ. Oral morphine for cancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007(4):CD003868

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Alert: Palladone extended release capsules (hydromorphone). 2005. Available at: www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety Last accessed 18 April 2012

- Shaiova L, Berger A, Blinderman CD, et al. Consensus guideline on parenteral methadone use in pain and palliative care. Palliat Support Care 2008;6(2):165-176

- Walker P, Palla S, Pei BL, et al. Switching from methadone to a different opioid: what is the equianalgesic dose ratio? J Palliat Med 2008;11(8):1103-1108

- Dart RC, Woody GE, Kleber HD. Prescribing methadone as an analgesic [letter]. Ann Intern Med 2005;143:620

- Loprinzi C. Supportive care. In: Cheson BD (ed). Oncology MKSAP. 3rd ed. Alexandria, VA: American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2004: 451-485

- Davies B, Sehring SA, Partridge JC, et al. Barriers to palliative care for children: perceptions of pediatric health care providers. Pediatrics 2008;121(2):282-288

- Mercadante S, Intravaia G, Villari P, et al. Intravenous morphine for breakthrough (episodic) pain in an acute palliative care unit: a confirmatory study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008;35(3):307-313

- Knotkova H, Pappagallo M. Adjuvant analgesics. Anesthesiol Clin North Am 2007;25:775-786

- Dolinsky C, Metz JM. Palliative radiation therapy in oncology. Anesthesiol Clin North Am 2006;24:113-128

- Fine PG. Palliative radiation therapy in end-of-life care: evidence-based utilization. Am J Hospice Palliat Med 2002;19(3):166-170

- Berrang T, Samant R. Palliative radiotherapy knowledge among community family physicians and nurses. J Cancer Educ 2008;23(3):156-160

- Weiger WA, Smith M, Boon H, et al. Advising patients who seek complementary and alternative medical therapies for cancer. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:889-903

- Raub JA. Psychophysiologic effects of hatha yoga on musculoskeletal and cardiopulmonary function: a literature review. J Altern Complement Med 2002;8:797-812

- Polubinski JP, West L. Implementation of a massage therapy program in the home hospice setting. J Pain Symptom Manage 2005;30:104-106

- National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care Consortium Organizations. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. Pittsburgh, PA: National Consensus Project; 2004

- Good M, Stanton-Hicks M, Grass JA, et al. Relaxation and music to reduce postsurgical pain. J Advanced Nurs 2001;33:208-215

- Schmidt C. Experts worry about chilling effect of federal regulations on treating pain. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97(8):554-555

- American Medical Association. AMA Statement on End-of-Life Care. Available at www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/about-ethics-group/ethics-resource-center/end-of-life-care/ama-statement-end-of-life-care.shtml Last accessed 3 May 2012

- Bagdasarian N. A prescription for mental distress: the principles of psychosomatic medicine with the physical manifestation requirement in N.I.E.D. cases. Am J Law Med 2000;26:401-438

- Swarm R, Abernethy AP, Anghelescu DL, et al. Adult Cancer Pain. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2010;8:1046-1086; National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Version 1.2010. Available at www.jnccn.org/content/8/9/1046.full.pdf+html?sid=d1544c2e-137b-4963-bd3c-25442dc21bf6 Last accessed 20 July 2012

Published: 17 June 2013